There was room for criticism, if you studied the numbers. In 1973, for instance, Tom Watson had finished 35th on the PGA Tour money list. Thirty-fifth. Pretty stout.

Then, over the first three months of the ’74 season, Watson made the cut in each of his 12 tournaments and was 16th in money earned as of March 31. Sixteenth. Positively stout.

Yet when the invites were delivered for the 1974 Masters, Watson wasn’t on the guest list.

Fuel to be fired-up? Some suggested Watson had a full tank. But here’s what he delivered when given a chance to speak his mind to a reporter in Kansas City: “They had a list of qualifications to abide by—win a tournament, make the top eight in the PGA, the top 16 in the Open. I didn’t win any tournament.”

In other words, Talor Gooch is no Tom Watson. Not as a golfer, not as a diplomat.

Many aspects of the golf world have changed in the last 50 years, but what was true in 1974 (as Watson understood) remains true in 2024 (as Gooch is clueless to)—it’s foolhardy, unprofessional, and unwise for future concerns to criticize Masters officials because you failed to achieve any of the qualifying guidelines. (There were 16 in 1974, there are 20 in 2024.)

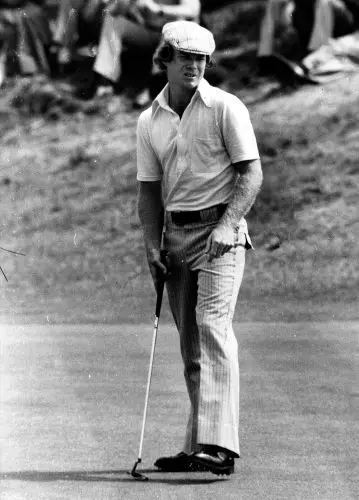

Eschewing such a rogue attitude, Watson in 1974 offered a glimpse into what would eventually help make him a global ambassador. Taking ownership of his failure to qualify, Watson promptly made sure the same thing would not happen the next April—he won the Western Open two months after the 1974 Masters.

Maybe Watson did not know what would be unleashed in his career (he would win 36 times between 1974–84). But he knew what his sense of comfort would be at Augusta National.

“I had a game that fit the golf course well,” says Watson. “I hit the ball high and (back then) I could chip and putt the eyes off it. I had a lot of tools working for me.”

It was the 1975 Masters that started a stretch of 42 consecutive starts in that major. But never has Watson overlooked the importance of his first Masters visit in 1970.

His spot had been earned by finishing T-5 in the previous summer’s U.S. Amateur, and at 20 he was afforded the chance to get all the “wow factors” out of him. The field included the likes of Gene Sarazen, Ralph Guldahl, and Jack Burke Jr., and, “I showed up to play the Par 3 and was paired with Gary Player and Gay Brewer,” says Watson.

“I was first struck by the beauty of the golf course, a manicured beauty. The flowers, the azaleas, the dogwoods. It was beautiful.”

Five years later, as a pro, Watson had a cameo role in arguably one of the greatest Masters ever. The iconic memory is of Jack Nicklaus’s monster birdie putt at the par-three 16th, the crucial play in his final round 68, -12 (276) total finish that earned him another Green Jacket at the expense of Tom Weiskopf and Johnny Miller, both of whom tied for second, one shot back.

But if you look carefully, you’ll see Watson on that 16th green, too. “While Jack made that putt and ignited roars, I was making a quad thanks to two balls in the water,” laughs Watson, Nicklaus’s playing competitor that day.

He would finish with a 73 for a -3 (285) total, good for T-8, but nothing was ever lost on Watson. “I was learning the course,” he says, and two years later he would turn the tables on Nicklaus with the first of his two Green Jackets.

Masters memories, some sweeter than others, all of them special. Now 74, Watson keeps adding to them.

“There’s always a sense of joy when you go to Augusta,” he says. “This year I’ll be going with my daughter, my son-in-law, and two grandkids (11 and 8) who will caddie for me in the Par 3.”

Since ending his competitive play in 2016 he has made the pilgrimage to soak in the Augusta atmosphere and for a third straight April, Watson will join Nicklaus and Player as honorary starters.

It is where he belongs, an icon among icons.

What makes Watson’s presence so fitting is the way his passion for golf burns as fervently as it did 54 years ago when the Stanford junior played the Masters for first time.

But whereas competition for decades was at the root of his passion, today Watson has a wider lens; his focus isn’t so singular. “I’m a golfer and golf has defined who I am. I love the game, but I’m trying to help the game. I want to get kids involved.”

Today, greedy and shallow golfers hide behind a mantra, “growing the game,” committed to a sense of duplicity. Watson walks a selfless and admirable route, committed to ownership.

Watson Links helps young golfers take the practice range lessons to the course with a mentor. “That’s how my father Ray started me,” says Watson, whose initiative is aligned with the First Tee program in five cities. “I want kids to discover the joy of hitting a really good golf shot.”

That may seem to be worlds removed from what Watson always wanted in his prime—to win golf championships at the highest level—but take it from the man whose 39 PGA Tour wins and eight majors cement his legacy: they are closely related.

It’s the circle of golf. In the beginning you are introduced to the game and shown how to play and savor it, then after years of being treated beautifully by golf, you know it’s time to give back.

Chalk it up to a sense of responsibility, which Watson has never been afraid to accept.