Long before most people heard of Tiger Woods, agents were circling the family home. Here’s what it was like, by the guy who first grabbed him by the tail.

Hughes Norton was once one of the most powerful men in golf. During his tenure as head of the golf division of Mark McCormack’s International Management Group (IMG), he was the lead agent for six world-number-one-ranked players, including both Greg Norman and Tiger Woods. Before Tiger ever struck a ball as a professional, Norton did deals with Nike and Titleist that brought him more than $60 million, a then-unprecedented sum for a professional athlete. Less than two years later—and for reasons never explained—Tiger fired Norton. McCormack then did the same, giving him a multi-million-dollar parachute tied to a 10-year non-compete clause and a gag order.

Now, for the first time, Norton is talking—about his clients, his boss, and his role in fostering the era of unbridled greed that now threatens to destroy professional golf—in RAINMAKER: Superagent Hughes Norton and the Money-Grab Explosion of Golf, from Tiger Woods to LIV and Beyond.

The book was written with LINKS’s editor George Peper, who has been a longtime friend (and while at GOLF Magazine was an occasional contract-negotiating adversary) of Norton. Published by Atria Books, a division of Simon & Schuster, RAINMAKER was released on March 26. The excerpt that follows describes the day Hughes first met a 13-year-old Tiger Woods.

Cypress, California, was as nondescript a town as you could imagine. Roughly twenty-five miles south of Los Angeles, it came into being in the late nineteenth century as a center of dairy farming. By the 1950s, the population numbered 1,700 humans and 100,000 cows. In the decade that followed, however, a housing boom in Orange County drove the bovines out as Cypress became a middle-class dormitory suburb. In 1989, it had roughly 40,000 residents—and one of them had attracted my full attention.

It was a balmy afternoon in September. I’d been on a West Coast business trip with a couple of IMG colleagues. That morning, after an abbreviated meeting in L.A. with the marketing people at Mazda, my two associates had hoped to catch an earlier flight back to Cleveland, but I’d cajoled them into dropping me off in Cypress before doubling back to LAX. Less than pleased, they’d taken the opportunity to give me some grief about what I was doing.

“How old did you say this wunderkind was—thirteen? What are we talking about here, Hughes, miniature golf?”

“Yeah, what are you two planning to do this afternoon, watch some cartoons, play Super Mario Brothers?”

I couldn’t argue with them. Stalking young kids was not my thing, although it had actually become common practice in IMG’s tennis division, as the prodigies in that sport were turning pro as early as age fifteen. Golf was another story. Nearly all the top prospects finished college (or at least high school) before trying for the Tour, and the teenagers who did go for it were usually flameouts. The lone exception had been Seve Ballesteros, who’d turned pro at sixteen, becoming the finest player Europe ever produced.

Besides, it wasn’t as if IMG Golf was hurting for clients, particularly at that moment. In June, Curtis Strange had won his second consecutive U.S. Open, and for the better part of seven years Greg Norman had been world number one. Meanwhile, the guys in IMG’s London office were killing it, having signed a powerhouse quartet of European Tour players—Nick Faldo, Bernhard Langer, Sandy Lyle, and Ian Woosnam—who collectively would win eleven major championship titles between 1985 and 1996. The truth was, IMG Golf was on a roll, and my own stock in the company had never been higher. We were back on top as the management firm uniquely suited for every major player, but always in my mind was the lesson Mark had learned from his own experience: “Never get complacent!”

Those words rang especially true now, since the landscape of our business had continued to evolve. Eight major agencies were focusing on golf with more than seventy players managed by firms other than IMG. Pro golf had grown into a high-stakes game, and the competition to represent elite players was intense.

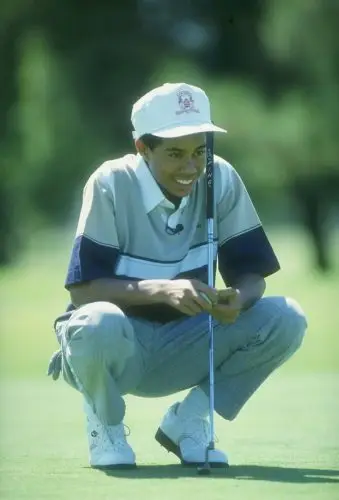

That’s why I was on my way to meet a thirteen-year-old. That and the fact that this particular thirteen-year-old with the curious name Eldrick “Tiger” Woods was clearly something special. I’d been tracking him for about five years, clipping newspaper reports of junior tournaments he’d won by several strokes while competing against boys two or three years older than he.

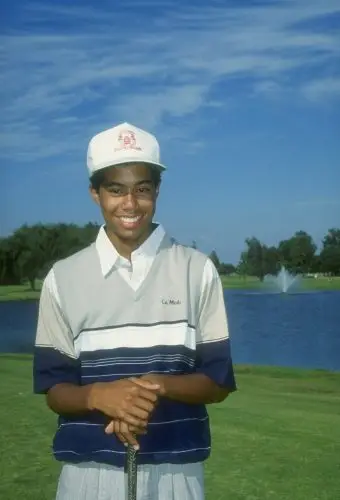

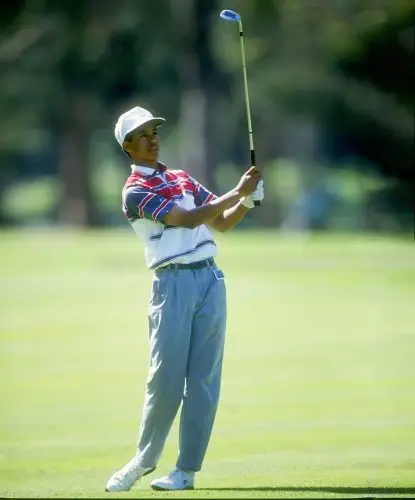

Back then, one of the major championships for kids was the Optimist Junior World held in San Diego. It attracted competitors from around the globe, and Woods had won it four times at various ages. But the event that had spurred me to find a Cypress phone book was the Big “I” Insurance Classic, where each year more than eight thousand boys ages thirteen to eighteen competed in local qualifiers to earn one of the 108 spots in the final, a seventy-two-hole stroke-play event. That summer—standing five foot five and weighing one hundred pounds—the thirteen-year-old Woods had not only qualified for the final but finished second, bettered only by Justin Leonard, nearly four years his senior.

Earl Woods had welcomed my call, but I wondered whether I was the first to make contact or other agents had beaten me to it. One thing I decided I was not going to do was make a sales pitch. After all, as good as this kid seemed to be, he wasn’t likely to turn pro for at least another five years—nine years if he finished college.

In those days, the junior qualifiers who made the thirty-six-hole cut got to play round three in the company of a PGA Tour player. Woods’s group drew a husky twenty-three-year-old rookie named John Daly—and on that day, after the first nine holes, Daly found himself three strokes behind Tiger. Only a birdie barrage on the second nine enabled Big John to save face. This kid truly seemed to be another Ballesteros, a once-in-a-generation freakish talent.

I arrived at 6704 Teakwood Street. A low-slung suburban ranch house, typical of that tasteful era that brought us lava lamps and bell-bottoms, it sat within a tract of several hundred similar homes, all one-story, none larger than two thousand square feet, no two of them separated by more than fifteen feet.

The Woods’s front yard was 80 percent driveway with a patch of grass about the size of a living room rug, and the home’s most salient architectural feature was its entry, where the A-line roof swept down to frame a facade of faux fieldstone evocative of a 1960s diner.

I hadn’t quite known what to expect that day. Earl Woods had welcomed my call, but I wondered whether I was the first to make contact or other agents had beaten me to it. One thing I decided I was not going to do was make a sales pitch. After all, as good as this kid seemed to be, he wasn’t likely to turn pro for at least another five years—nine years if he finished college. I was there mostly to listen. That worked out just fine, as it quickly became apparent that Earl Woods loved to talk, and his favorite subject was his son.

He was a burly guy with an outgoing personality, a former military man who liked being onstage and in charge, while his diminutive Thai wife, Kultida, was reserved. We had barely settled into our seats in their living room when Earl launched into a detailed recitation of Tiger’s remarkable path in golf, beginning with what, I would come to learn, was one of his go-to stories.

“I’m in the garage, banging balls into a net, and Tiger’s there with me, sitting in his high chair. He’s ten months old, but he’s watching me wide-eyed, mesmerized, really into it. So I unstrap him and have him come over with me. He picks up a cut-down club I’d made for him as a toy, puts a ball down, waggles, and hits it smack into the net—first time! I shouted to Tida, ‘Honey, get out here—we have a genius on our hands!’”

Earl then rhapsodized on what had followed: Tiger at age two hitting balls with Bob Hope and Jimmy Stewart on The Merv Griffin Show; making his first hole-in-one at age six, breaking 80 at age eight, breaking 70 at twelve, etc. Tiger had by that time won more than 150 junior and amateur events.

Throughout all this, Tida had remained silent, but when Earl finally took a breath she spoke up. “Tiger a good student, too. He no get good grades, Mom put his golf clubs in closet.”

Short and to the point. As I would learn in the years to come, it was Tida Woods who was often the tougher parent, the disciplinarian. Earl liked to project the image of a hard-ass taskmaster, but when push came to shove in the Woods household, it was invariably Tida whose will prevailed.

They were an unlikely couple, Earl and Kultida Woods, two people who had found each other, as many couples had a generation earlier, through the harsh exigencies of a war.

Earl had grown up in Manhattan, Kansas, and attended Kansas State, where he’d played on the baseball team. After graduation he’d spent twenty years in the army, including two tours in Vietnam, where he’d become a highly decorated Green Beret and risen to the rank of lieutenant colonel.

Back then, after doing a stretch in the war zone, soldiers were allowed a week of R&R, which could be spent in any of several locations in Asia. Most of the American troops opted for Australia, and why not, it was a land where English was spoken, the beaches were beautiful, the bars plentiful—the perfect place to let off some steam.

Not Earl Woods, and for a valid reason. In those days, African American GIs were not made to feel very welcome in Australia, as an attitude of white supremacy had sadly lingered. So he opted instead for Thailand, and it was there in 1966 that he met Tida. Three years later they were married.

What surprised me as I looked around the room was a conspicuous absence of trophies. “They’re gone,” said Tiger matter-of-factly. “By the time I hit eleven, there were a hundred and thirteen of them around the house. Mom made me give them all away. I don’t care.”

Every time I think of the way they met, I marvel at the power of fate, the almost supernatural force that predetermines how so many aspects of our lives—and the lives of others—play out. Consider that, if Earl hadn’t made that trip to Thailand, there would be no Tiger Woods.

I’d been speaking with Earl and Tida for about forty-five minutes, when suddenly the front door opened and in walked Tiger, all five-five and one hundred pounds of him. As we shook hands, he flashed the toothy grin that is now world-famous. He was a polite and respectful little kid, if a bit shy, often looking downward as he spoke. But at the same time there was a quiet self-confidence.

We made small talk for a few minutes and then Tiger took me back to his room. At the threshold I noticed, penciled into the left side of the door frame, the classic series of hash marks and dates parents use to record their child’s growth over the years. To Tiger, however, I think those notches probably signified more than that. They were a way of keeping score, assessing his development with a series of irrefutable numbers, like a golf handicap. My bet is that he was watching those ascending pencil marks impatiently, yearning to hit six feet plus, as he knew a more powerful physique would make him a more powerful golfer.

His room was typical for boys his age with posters on the walls, except that, instead of rock idols or NFL quarterbacks, Tiger’s heroes were golfers—Jack Nicklaus, Greg Norman, et al.—and tacked on one wall was a now-famous clipping from Golf Digest.

Following Nicklaus’s victory in the 1986 Masters, the magazine had compiled a list of his career accomplishments, including his age at the time of each achievement. Tiger back then likely was not thinking about major championships, but he was laser-focused on Jack’s feats as a junior and amateur golfer—and on hitting each mark at an earlier age. So

far, every box had been ticked.

What surprised me as I looked around the room was a conspicuous absence of trophies.

“They’re gone,” said Tiger matter-of-factly. “By the time I hit eleven, there were a hundred and thirteen of them around the house. Mom made me give them all away. I don’t care.”

Wow, I thought, how many thirteen-year-olds would agree to that? Then it hit me, this kid was more focused on the process—the grind, the ball beating, the competition. Prior accomplishments meant little to him. The only important trophy was the next one.

My actual face time with Tiger lasted only a few minutes, and then Earl, Tida, and I returned to our seats in the living room. I was sitting by a window, and a few moments later, out of the corner of my eye, I saw Tiger on his bike, pedaling off down the street. Taking that in, I thought, Welcome to the tennis world.

As the conversation continued, I gave Earl and Tida a quick history of IMG, and they let me know that no other agents had approached them. That was a good feeling, but at the same time, the situation in which I now found myself was different than with any prospective client I’d ever approached—different in an awkward way. Given the nearly thirty-year gap between my age and Tiger’s, most of my future dealings would be not with him but with his mercurial father.

Just before the visit ended, Earl made a couple of emphatic points. “Number one,” he said, “this kid is gonna change the world—not just the golf world but the world. Number two, he has something to prove. I can’t tell you how many times Tiger and I—as the only two Black people traveling the junior circuit—have walked into country club grillrooms and felt the chilly silence of the assembled white folks. I told Tiger to learn a life lesson from those moments: forgive, but never forget.” Earl was counting on Tiger to use those dark memories to fuel his fire to become the best golfer the game had ever seen.

As we walked to the door he said, “The first Black superstar in golf is going to make himself and someone else a whole lot of money.”

“That’s why I’m here, Mr. Woods,” I said. “That’s why I’m here.”

Thank you for supporting our journalism. If you prefer to read in print, you can also find this article in the Spring 2024 issue of LINKS Magazine. Click here for more information.