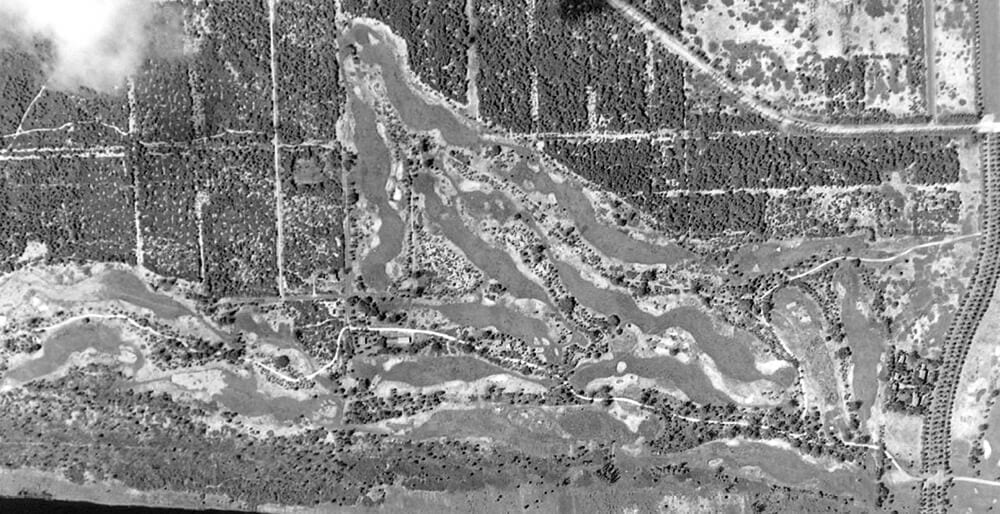

One of golf’s most architecturally significant courses, The Lido, is being reborn in the sands of central Wisconsin. The original C.B. Macdonald design on the coast of Long Island was parceled off during the Great Depression and finally lost for good during World War II after the U.S. Navy took over the property as a strategic defense site. The revered layout is now getting a second life thanks to Tom Doak and the Keiser family, who are seeking to faithfully recreate The Lido on a sprawling property adjacent to the Sand Valley Golf Resort.

Golfers are a nostalgic sort, a passionate segment of them anyway, which speaks to the game’s history and traditions. And there’s a particular fascination when it comes to courses themselves. The playing fields in golf are endlessly distinctive, colorful works of landscape art created by different architects and in different eras. Golf courses have their own special charms, some of those unique to the players themselves and their personal experiences.

While some have dismissed the idea of trying to bring back a historic course like The Lido, most sentiment seems decidedly in favor of trying to give new life to a creation that Hall of Fame golf writer Bernard Darwin once called the finest course in the world. The original wasn’t simply discovered; it was very much man-made, with massive earthmoving required on the swath of seaside swampland.

The vision for the new Lido inspires the question, which other extinct courses would golfers love to see reborn?

Some might be entirely dependent on their setting (and therefore perhaps almost impossible to recreate), while others might have significant architectural significance. Many will surely be old—like the private 9-hole Ocean Links in Rhode Island built in the 1920s by Macdonald and Seth Raynor across from Newport Country Club—but some may be of more recent vintage; consider that Doak’s very first design has now been turned into a commercial hops farm. And some golfers might cast their eye globally. No doubt just seeing images of the now-closed Stone Forest in China has elicited a yearning to experience that visual stunner of a course. Of course, other golfers will have more personal ties to a now-extinct course they once knew.

To start the conversation, here are a handful of U.S. courses shared by author Daniel Wexler, who years ago wrote the book Missing Links: America’s Greatest Lost Golf Courses and Holes.

Timber Point (New York)

The original design from Harry Colt and C.H. Alison, built in the early 1920s, was celebrated as a mixture of Pine Valley and National Golf Links of America, with water on three sides and vast expanses of sand. The green of the short par-three 12th hole was completely encircled by a sea of sand, while the long, uphill par-three 15th played to an elevated green backed by the bay and surrounded by more sand hazards. A version of that hole, Gibraltar, still remains at the scenic, but much-altered 27-hole municipal facility. Wexler calls it a “skeleton” of what was there, as the original was converted after being sold more than 60 years ago.

El Caballero (California)

In the San Fernando Valley, there’s a course by the same name adjacent to the original El Caballero site, which is now all upscale residences. Billy Bell crafted the layout in the 1920s, likely with some input from noted architect George C. Thomas, with whom he worked regularly. The course played through two large canyons in the foothills of the Santa Monica Mountains, with stylish bunkering, plentiful foothill vistas, and a variety of demanding uphill and downhill holes. Esteemed sportswriter Grantland Rice rated it as one of the best on the entire West Coast.

Mill Road Farm (Illinois)

Another Flynn design from the 1920s, Mill Road Farm was a private estate course built outside Chicago for Albert Lasker, who was regarded as the father of the modern advertising industry. Wexler called it a “monster of a golf course without being tricked up,” as it stretched over 7,000 yards as a par 70 in the age of hickory clubs. There was no water and it wasn’t heavily treed—just a long, heavily bunkered brute with a lot of great green complexes. Lasker put up $1,000 if someone could break par and it took almost a decade before Tommy Armour collected by shooting a 69. Some say he was the only player to do so.

Boca Raton South Course (Florida)

The original South Course at the Boca Raton Resort and Club, which was sold sometime after World War II, was probably as good as anything architect William Flynn did except for Shinnecock Hills, according to Wexler. It was routed across a massive, sandy property that’s now home to the Royal Palm Golf and Yacht Club, which has an expansive residential development and a Jack Nicklaus course that has no connection to the original. “I always say it was the only thing that could have pushed Seminole in Florida before the war,” Wexler said of the South Course. “It was 6,600 yards and change, which in the 1920s was big. And there was room to lengthen. That could have been a big-time golf course today.”

Fresh Meadow (New York)

The old Fresh Meadow Country Club was an original and much-revered A.W. Tillinghast design located in Flushing, in the borough of Queens. It was among a number of great courses in Queens that were sold off when real estate around New York City simply got too expensive and the clubs that owned the land moved out to Long Island. Gene Sarazen was the first head professional at the original Fresh Meadow, which hosted both the 1930 PGA Championship and the 1932 U.S. Open (which was won by Sarazen).

Royal Palms (California)

On the southwest corner of Los Angeles County’s Palos Verdes Peninsula, Bell built this dramatic private course on steep terrain atop coastal cliffs. Several holes crossed deep chasms and the views over the Pacific Ocean from high up the hillside were jaw-dropping. The par-four 18th hole hugged the precipitous clifftops, making for one of the most dramatic finishers anywhere. The course closed in the Great Depression and, not unlike the original Lido, it was taken over by the military for gun placements during World War II. “That’s a golf course that almost no one in L.A. remembers,” Wexler notes. “I don’t know that it was as good as these others tee to green, strategy-wise, but the setting was just mind-boggling. It might be impossible to replicate, unless you found someplace in New Zealand that had available land.”

Are there golf courses no longer in existence you would love to see get new life?