It’s been 50 years since the USGA turned the West Course at Winged Foot Golf Club in New York into a golfing minefield. The course setup isn’t the only remarkable memory of the 1974 U.S. Open, though.

A flushed long-iron approach at the 72nd hole to secure a major championship tends to be spoken of with reverence as such a shot at such a time requires a combination of skill and nerve beyond most players. Ben Hogan’s 1-iron to the 18th green at Merion in the final round of the 1950 U.S. Open; Jack Nicklaus’s 1-iron at Baltusrol’s home hole in 1967; Tom Watson’s 2-iron at Royal Birkdale in 1983; and Nick Faldo’s 3-iron to the last at Muirfield nine years later are shots of which only golf’s absolute elite are capable.

Another that probably deserves similar recognition is Hale Irwin’s second to Winged Foot’s 18th at the 1974 U.S. Open, a shot that more or less guaranteed him his first major victory.

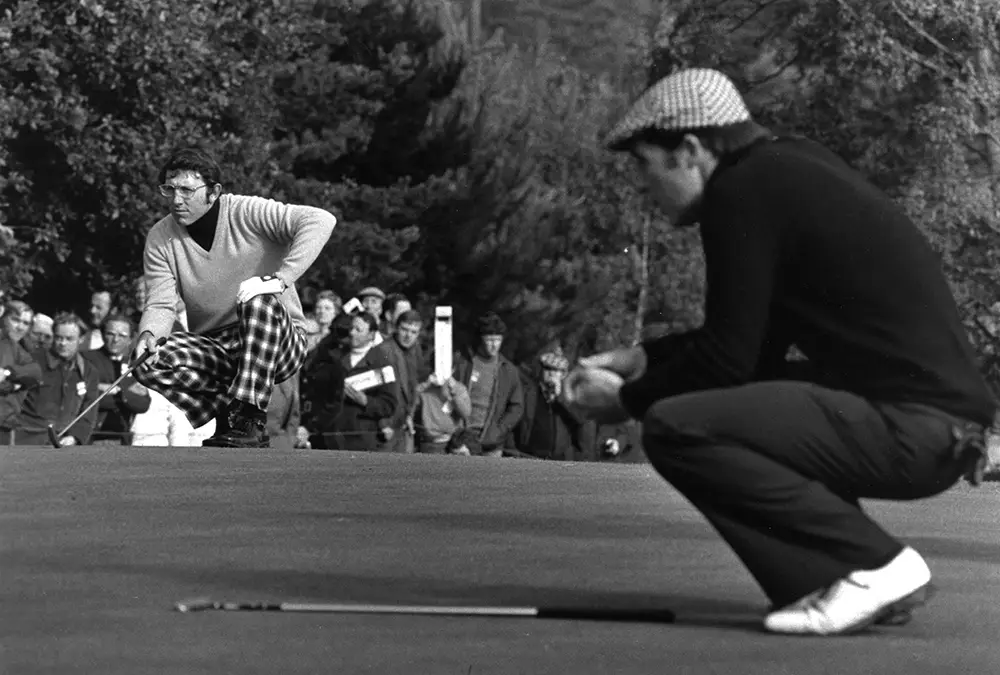

The 29-year-old native of Joplin, Mo., had a two-shot lead over Forrest Fezler standing on the 18th tee, but didn’t know it. “There were very few scoreboards around the course,” Irwin remembers, “so I didn’t know where I stood.” Irwin had holed a crucial par putt at the 17th to maintain a one-shot advantage and been told by a marshal on the 18th tee that Fezler had closed with a five. But he didn’t want to rely on unconfirmed intelligence, so played the 18th thinking he was probably one in front—a nervy scenario given how difficult the hole was. Irwin had 194 yards to the pin with a little breeze hitting him from the left.

Never a bomber, Irwin had built his game on sound course management, a wide variety of shots, patience, and the quiet determination he’d shown as a 6-foot-1-inch, 180-pound safety on the University of Colorado football team. “I was even a little guy back then,” he once told the Denver Post. “I had good football speed, but not flat-out speed. So, I had to be in good position and play technically better than the next guy. And I had to play over my weight.”

He had finished in the top 10 in the previous two majors and, after six seasons on the PGA Tour, had recorded two wins—the 1971 and ’73 Sea Pines Heritage Classic at Harbour Town. And because he had become so adept with every club in the bag, Irwin considered the long irons almost as scoring clubs.

He hadn’t yet felt the pressure of closing out a major championship, but knew he had the shot that faced him at 18. “I’d hit a lot of good 2-irons that week so felt pretty confident,” Irwin says. “I made a good swing and hit what was definitely one of the most satisfying shots of my life. I really felt it.”

The ball pitched just short of the hole and rolled about 20 feet past. Three putts would’ve been good enough to win, but he needed only two. Tom Watson, Irwin’s final-round playing partner, was hugely impressed. “Hale hit the most pure 2-iron you’ve ever seen,” Watson said. “Right over the flag. Just beautiful.”

You’d think a shot like that would get plenty of YouTube hits and still be talked about with a deep appreciation. But it barely gets a mention when the game’s great plays are discussed. Irwin, though, is neither disappointed nor surprised.

Despite finishing his career with three U.S. Open victories, 83 professional wins including 20 on the PGA Tour and 45 on the Seniors/Champions Tour, plus a well-deserved spot in the World Golf Hall of Fame (inducted in 1992), Irwin never regarded himself as a true great. “I was just trying to be the best I could be,” he says. “Be as good as players like Nicklaus, Palmer, Player, Watson, Ballesteros, and Faldo.” Because he never quite got there, Irwin understands why his shot at Winged Foot isn’t remembered like some others. “And I’m not really sad about it because I know how good it was, and that’s really all that matters.”

Of course, Irwin’s place in the game isn’t the only reason his shot is given scant recognition. Were it the only talking point from that particular championship, or had Hogan or Nicklaus hit it, perhaps it would have received the lasting acclaim it deserves. If Irwin’s performance is remembered at all, though, it gets only a fraction of the attention given to the course and how the USGA/Superintendent Ted Horton had set it up.

Stories about the length of the rough (“Legitimately six to 10 inches long,” said defending champion Johnny Miller), narrowness of the fairways, position of the pins, and speed/firmness of the greens are legion. The title of broadcaster Dick Schaap’s book about the tournament, The Massacre at Winged Foot, gives a clear indication of how those elements combined to create so brutal a test—one that produced a tournament scoring average of 76.73 and only eight sub-par rounds. The cut fell at +13 and Irwin’s winning total was 287 (+7).

The consensus was that the setup had been a direct response to the 8-under 63 Miller had shot in the final round at Oakmont the previous year. Sandy Tatum, a USGA Executive Committee member and the man ultimately responsible for the course, wasn’t having it, though. He said he regretted nothing and famously added he hadn’t been trying to embarrass the world’s best players but simply identify who they were.

True or not, Irwin says he never experienced anything like it again. “During my career, nothing approached that level of difficulty,” Irwin says. And though his last appearance in the championship came in 2003, Irwin insists he’s never seen anything as severe again. “The 2006 version of Winged Foot where (Geoff) Ogilvy won, and Oakmont where (Angel) Cabrera won the following year, came close. But they were using very different equipment which meant those courses played nowhere near as tough.”

Irwin doesn’t expect Pinehurst No. 2 to be anything the players can’t handle, either. “It’s a great course,” he says, “but effectively plays a bit wider than some other older courses. I think the group of potential winners is probably larger than it would be elsewhere.”

Irwin wouldn’t be surprised, in fact, if it threw up another Martin Kaymer (winner in 2014) who was ranked 28th in the world at the time, or even Michael Campbell (2005) who was 80th. “I think this could be another tournament where a lesser-known player wins,” he says.

At 448 yards (subject to change), No. 2’s final hole is exactly the same length as Winged Foot’s 18th was in 1974. But, of course, it’s unlikely that whoever does win in 2024 will need to hit an Irwin-esque 2-iron into the final green.

Is the U.S. Open your favorite major championship? Tell us your thoughts in the comment section.