In 2012, then Ping CEO John K. Solheim made headlines when he approached golf’s distance issue with a “three-ball solution,” suggesting that governing bodies adopt a set of new “Ball Distance Ratings” for not only the spheres we use right now, but also hypothetical new models that travel both thirty yards longer and shorter than those currently on the market.

Solheim’s concept generated some conversation but quickly received a polite Heisman from U.S. Golf Association executive director Mike Davis, who was quoted in Golfweek as saying, “We have a longstanding belief, going back more than 100 years, that one set of rules for all golfers is one thing that has made the game so strong.”

This position doesn’t exactly seem ironclad considering that at the PGA Tour or USGA championship level all competitors (if I understand Solheim’s vision correctly) would be playing the same type of golf ball—whether it be juiced-up, rolled-back or the same old Pro V1s and Pentas we all know so well. It might annoy the players and caddies, but “one set of rules” would still be intact. Maybe the USGA considers the notion of developing (much less enforcing) Ball Distance Ratings an unnecessary complication, but the effect of the position is to slam the door on innovation in terms of how our fields of play are defined.

If it’s possible for the golf world to put aside the professional game for a moment, Solheim’s idea bears further examination. It’s obvious that rank-and-file golfers would flock to a ball that leaves the current Pro V in the dust, though some critics and architects have shuddered at the impact these super-charged orbs could have on the safety of our golf courses. One well-respected architect, on the other hand, suggested that at the club level at least, women’s events might be improved by a longer ball.

My imagination, however, has for some time been considerably more intrigued by the concept of the shorter ball. When John Solheim writes that “it is far simpler to adjust the ball to the course, than to adjust the course to the ball,” he’s not wrong. He’s thinking of classic courses bending over backward to find yardage and in some cases butchering their designs to defend against the modern game. But it’s possible that with the right product in place, a distressed course or an innovative developer could create something positive through adjusting the course to the ball…by becoming smaller. This concept is counter-intuitive given that distance is only a real issue at the elite levels of the game—most of us find the game plenty challenging as it is. The problem is that new courses almost always proceed under the assumption that the bombers must be accommodated—a host of planning decisions spool out from this point to create those way-back tees that most of us don’t use.

Every year, the National Golf Foundation or some similar organization releases yet another study outlining the symptoms of why golf is stagnating. You’ve heard them all before. It’s too hard. It’s too expensive. It takes too long to play. I’m not sure much of anything should be done about the first point—once bitten by the bug, real golfers love the game because of its difficulty, not in spite of it. But the second two points can be addressed—effectively—by the shorter ball.

More on that later, though. One of the many heartbreaks of the Crash of 2008 has been the impact it has had on golf course architecture. It’s true—there’s been a silver lining. We’ve seen some excellent renovations to our classic courses, readying them for a new century of play, and architects are getting creative about “recycling” undistinguished existing courses into new layouts worth playing. (Think of Renaissance Golf’s CommonGround, built on a former Air Force base near Denver, or Bobby Weed’s great work at the Deltona Club, north of Orlando.) But new course construction is all but extinct. That’s likely to remain so until the next speculative bubble inflates.

Golf has simply become too land-intensive to consider for all but the wealthiest developers in the rosiest of economic times. It’s almost impossible to find 220 acres near a major metro area in 2012—indeed, this was even the case two decades ago, thus leading to the Bandon-Sand Hills wave of “Field of Dreams” courses. It’s hard not to have deep suspicions about the long-term viability of this model. Bandon will be fine, of course, but other remote destinations have struggled. That’s likely to continue.

Let’s take a moment to consider the possibilities a shorter ball would open up for both new construction and those seeking to “recycle” an existing course. How many prime sites would become viable for developers if their initial land costs were cut by 50 percent or more? What if you could find a world-class site for golf within ninety minutes of Manhattan, with the only caveat being that it was only 70 acres? And, most importantly: What if the course that was built on that little site was nevertheless so bold and exciting that it would be impossible to deny the thrill of playing it?

It’s taken as an article of faith that Americans like Big Things—unless the free market dictates otherwise, we’ll buy Hummers all day long. But the market did exactly that to the Hummer—it buried it—and the same thing is happening in golf. Gigantism. To create venues to suit the modern equipment and ball, developers face enormous land costs, huge construction, commodity and maintenance budgets—all expenses that are finally passed along to the consumer, who in turn chooses to find some other way to spend his leisure dollar.

Imagine a different type of course. What if you had all the beauty and terror and architecture of a Pine Valley, only in a 5,000 yard package? At this course, members and/or visitors would be given two options of play:

Modern equipment + rolled-back ball. Same nice feel of the modern ProV, but with 80 percent of the flight.

Hickory clubs (vintage or replica), + current ball. Sold in the shop AND loaned out for free right on the first tee.

I can hear the brakes squealing. One would absolutely be forgiven for thinking that this article has gone off the rails at the mere mention of hickory golf. We’ve now entered the province of the eccentrics, the Civil War re-enactors of golf, right? Well, maybe. But playing hickory can teach us some valuable lessons, not the least of which being the mutability of how we perceive the scale of a landscape. It’s determined by the relationship between the size of the golf course and the capabilities of our equipment—clubs and ball.

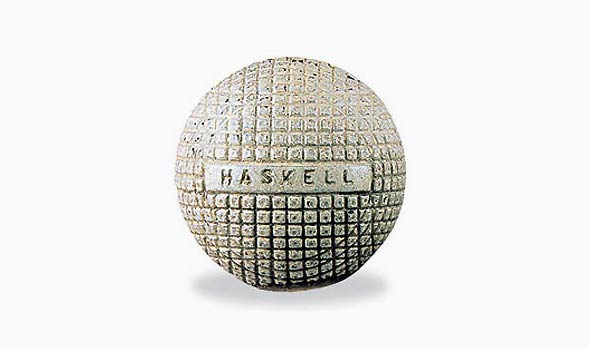

This past spring, I played a little 2,000-yard jewel box of a course near St. Andrews called Kingarrock. The experience felt straight out of an episode of Downton Abbey. The course was designed to be played with hickories and the vintage Haskell ball. After playing a few holes, I looked at a 300-yard par-four in exactly the same way I would a 400-yarder using all modern stuff. And on the one occasion that I outdrove my playing partner, I felt exactly the same way I would have otherwise.

Since my visit to Scotland, I’ve kept in touch with David Anderson, Kingarrock’s proprietor. He told me a great story a couple of months ago. A South African touring pro (not one of the household names) visited and played hickory over the summer. After his round Anderson asked him if he’d enjoyed himself. The pro said yes, adding that the most refreshing thing was that for a change he could actually see his ball land in the fairway. That’s the game they play. And we could play it, too, under Solheim’s three-ball solution. The manufacturers would adore the idea of Joe Sixpack bombing it 330—they’d sell a shocking number of golf balls. But this is the sporting equivalent of the Navy launching missiles off the deck of a cruiser in the Indian Ocean to a target in tribal Afghanistan…without any kind of guidance system to speak of. The profit motive behind the shorter ball, on the other hand, is nil at the moment—for the equal and opposite reason. But I really wonder if a good limited-flight ball wouldn’t bring back some of the sporting nature of golf without sacrificing its fundamental qualities.

A counter-argument, anticipated: Some readers will doubtless recall the unpromising precedent of the limited-flight Cayman ball, which had no less of a luminary than Jack Nicklaus as an advocate. Developed by MacGregor engineers in the 1980s for a land-challenged Golden Bear course on Grand Cayman Island in the Bahamas, the concept never took off. Today, one is most likely to find these brambled oddities at a shoehorned-in driving range.

The Cayman was a bridge too far not because it was a bad idea, but because it didn’t match with our baseline expectations (as opposed to wildest dreams) of how long a well-struck shot should travel. The Cayman’s 50 percent distance turned a driver into a 9-iron or pitching wedge. This is the golf equivalent of playing Wiffle-Ball. By comparison, the various iterations of the Haskell ball played during the first three decades of the 20th century traveled about 75 percent of what we expect today—Bobby Jones could put a charge into one and go deep, even by today’s standards. That was baseball. In 1980, the first year the statistic was officially recorded, Dan Pohl led the PGA Tour in driving distance with an average of 274.3. This represents about 86 percent of the 318.4 yards averaged by the 2011 leader, J.B. Holmes. Using today’s equipment, we’re playing college baseball—or, to put it less charitably, Little League. With that in mind, does an 80 percent ball—available for those who wish to play it—sound all that radical?

Imagine a group of guys—low markers—heading out on a Saturday morning to their 5,000-yard preserve. Maybe this is a new course, or maybe it’s a recycled ’90s “Country Club for a Day,” re-routed and rebuilt to eliminate playing on land ill-suited for the game. Armed with their modern clubs and a sleeve of Titleist “80%s”, they stripe 200-yard drives, confront daunting hazards, and play feathery approaches into the most imaginative new greens. These golf holes have been built with extra care by the best architects alive, who are thrilled simply to not be working in China for a change. This course, “Little Pine Valley,” is a short walk, so the guys are done and back to their families in a little over three hours—because it also happens to be located in a place where people actually live. Best of all, they might even make plans to come back the next day, because this club—private or public—was developed at a fraction of the price of the Big Course up the street.

Who’s going to have the nerve to tell that foursome that what they just did was something less than “Real Golf”? Would they be such mindless sheep as to believe them? Or would they just laugh?

Certain golfers, of course, would enjoy tackling “Little Pine Valley” with both modern equipment and the modern ball. This would be a great course at which to be a woman, a senior or a kid just starting out. Even better, everyone could play from the same tee, the way our ancestors did for so many years. Solheim favors this concept, and I’m in his camp. Even if his Ball Distance Ratings are deemed unworkable for handicap purposes, wouldn’t this be just a tad more natural—and more sociable—than the way it is now? When you look at a glamorous magazine photo of a golf hole, do those five tee boxes stretched halfway to the horizon really appeal to the eye? We’ve gotten used to them because they’re considered necessary, of course—but are they actually good?

Unfortunately, if the comments in the Golf Digest post about Solheim are any indicator, the biggest obstacle to a “Little Pine Valley” may be the mindset of the American golfer himself. It’s telling that the revulsion toward Solheim’s three-ball solution is directed mostly toward the shorter ball. Here’s a representative comment: “This is the most ridiculous idea I’ve ever heard of. Why practice your golf swing, seek instruction, work out? So that you can play a ball that doesn’t go as far…huh?” This kind of thinking is, in a word, narcissistic. It’s been said that in golf, power is its own advantage, and that has held true from the days of Young Tom Morris through to Jack Nicklaus and all the way down to the young bombers of the current moment. But power is solely derived in relation to what one’s fellow competitor possesses—Alvaro Quiros is going to outdrive everyone, regardless of whether the ball is geared to fly 250 or 750 yards. The landscape itself is quite indifferent to how far we can bomb it.

What it boils down to is this question: Would American golfers prefer to continue playing overpriced, five-hour rounds on penal, often environmentally-challenged courses simply because of an addiction to those moments—and for most of us, they happen only a handful of times each season—when the planets align, we make a perfect strike and bomb it out toward the 300-yard mark? Are we willing to sacrifice an entire generation’s worth of innovative new course design simply because golf’s governing bodies want us to believe we’re playing the same game that we see on TV?

Another Golf Digest commenter wrote: “Why don’t we make baseball parks shorter each time David Epstein [sic] or any other little guy is at the plate!” Leveling the playing field is not what this is about—popcorn hitters will continue to be thus with a shorter ball. I made a baseball analogy earlier; let’s extend it. Some amazing courses emerged during the construction boom of the ’90s and early ’00s, but the majority were the golf equivalent of Veterans Stadium—artificial and devoid of charm. We’re not building much of anything right now in this country, but when we do, we should consider building Fenways and Wrigleys—smaller arenas with character to burn.

The future of golf is not a zero-sum game, and the 80 percent solution is not about replacing the modern golf ball. It’s about the game’s governing bodies legitimizing—and the manufacturers developing a market for—an alternative to golf that is still Real Golf. We don’t want Hummers anymore, and unless we’re playing on TV, we don’t need 7,400-yard stadium courses, either.

There’s more than one way forward.