How the most recognized course in golf is dealing with golf’s most recognizable issue

There are not many golf courses as well positioned as Augusta National to survive the distance onslaught. As the world’s best players continue to play a longer game each year, and as golf’s governing bodies now appear to have reached a crossroads in their willingness to turn back the clock on technology, the perennial home of the Masters becomes even more interesting to watch as a laboratory for the game.

The data at one level are simple. Back in 1980, when the PGA Tour started measuring things, the average drive on Tour was 256.5 yards. The top 10 players averaged 270.9, and the longest driver was Dan Pohl at 274.3. Jump to 2020 and the average drive became 296.4 yards (a hike of 15.6 percent). The top 10 players were at 314.6 (16.1 percent longer) and the longest hitter was Bryson DeChambeau at 322.1 yards (17.4 percent longer). During that same time, Augusta National had been stretched only 8 percent, from 6,925 to 7,475. In other words, only half the additional distance that a drive now travels.

The anecdotal evidence of a course playing some 500–600 yards shorter than it did 40 years ago is seen in the clubs the players are hitting for approach shots. A golf course originally designed to handle middle and long irons into many greens is now regularly attacked with short irons during the Masters. Tiger Woods’s legendary display of power during his runaway win in 1997 showed how vulnerable the course was to the power game; he never hit more than a 7-iron into a par four all week. Small wonder the course was subsequently lengthened, though not enough, as it turns out. Today, it is common to see very short irons and wedges into most of the par fours—and in some cases, the par fives.

Of course, part of the issue is club design; your average iron has 4–6 degrees less loft now than a few decades ago, which effectively turns today’s 7-iron into what used to be called a 5-iron. Yet because of increased sole weighting, the club delivers considerable loft at takeoff, allowing the ball to come down from a higher point with less spin.

In the early years of his dominance at Augusta National and elsewhere, Jack Nicklaus was so much longer than everyone else on Tour that he sometimes might hit a short-iron second shot into the par fives at Augusta National. But the trend now is unmistakable, affecting far more players than ever. What’s a golf course to do?

With the USGA and R&A having recently followed up their 2020 Distance Insights Report with word that they are likely to implement some sort of (as yet to be determined) equipment rollback, there’s good reason to look closely at how Augusta National has handled the issue over the years.

For one thing, the club has never stood still. After all, no course in the world is more exposed to the ongoing discourse of distance. Since first holding what became the Masters in 1934, Augusta National has been the most closely watched platform with the longest continuous record of championship play. It’s also been one of the most tinkered-with major venues, sporting a record of continuous tweaking, adjustment, and response to how the game is played at the elite level.

No hole has been spared the touch of renovation or modernization. Of the original 24 bunkers on the course that Alister MacKenzie and Robert Tyre (“Bobby”) Jones installed at its inception in 1933, only one such hazard remains in its original position: the fairway bunker on the 495-yard, par-four 10th hole, and that used to be greenside until the putting surface was moved 40 yards downfield in 1937.

If it seems that the par-72 course, now measuring 7,475 yards, remains vulnerable, that’s because it is. The fairway corridors are uncharacteristically wide for major play and are framed by “first-cut” rough at a height that is unusually kind to those who miss the central landing lanes. With four par fives that are now all readily in reach with long and middle irons for elite players, the course rewards length to an unusual degree. If ever a course would seem on the verge of obsolescence in the face of the distance issue, it would be Augusta National.

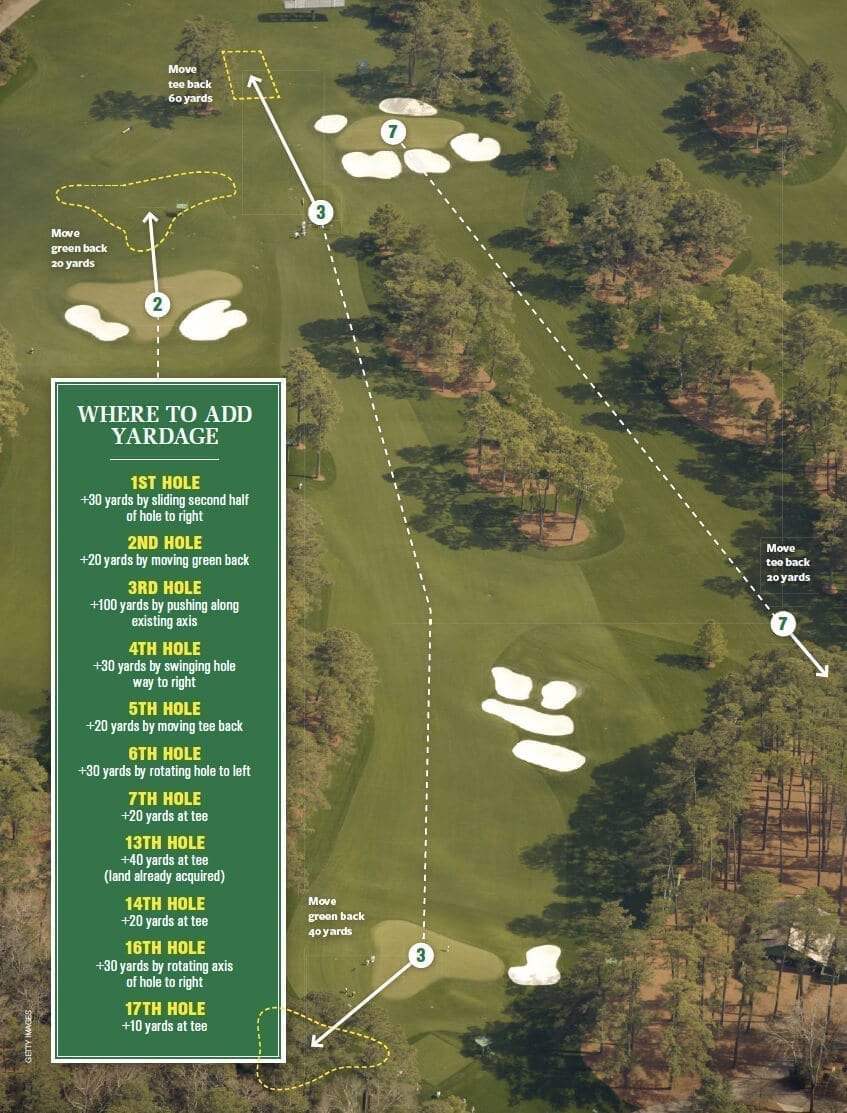

If the club’s managers wanted to, they could turn the course into a 7,800-yard track. (For the record, club chairman Fred Ridley did not respond to an inquiry about this. Neither would anyone else associated with the club.) Consulting architect Tom Fazio and his longtime associate Tom Marzolf have been working on the course for years, with detailed plans for every hole stacked away in club files; the terms of these proposals are not a matter of public record. But any armchair architect could figure out a way to add, say, 350 yards. It would come at considerable cost, since it would entail moving some greens back and, in some cases, entire holes laterally.

The sidebar on the facing page details the stretches, seven of them occuring on the first seven holes, for an additional 250 yards, with another 100 yards addable to four holes on the inward nine.

This is highly speculative stuff, of course, and the benefit-cost analysis here would be fascinating to see. Having spent—as a matter of public record—upwards of $20 million to obtain a five-acre parcel from the adjoining Augusta Country Club left of the 11th hole and behind the 13th green, Augusta National has shown it is not shy about acquiring property on its perimeter. In all likelihood, a new back tee for the 13th hole will be in place for the 2022 Masters, allowing that hole, at 550 yards, to require an extremely precise drive between the creek on the left and the woods to the right if players are going to have a go at the green in two.

An ambitious land plan, including public works improvements to the city of Augusta, has already enabled the club to acquire much of the land to the west of its original property out to Berckmans Road. The result has been a much-expanded infrastructure and park-like atmosphere that yields the greatest spectator experience in golf. It shows that the folks running the show are pretty smart when it comes to long-term planning. This is the club, after all, which picked up its entire range and moved it across the entry road, converting what had been a pretty desultory place for banging golf balls (into an ungainly boundary net) into one of the game’s premier warm-up and training facilities.

While distance is always an advantage, precision, control, and emotional discipline are also traits that Augusta National requires. And it’s not as if long hitters have totally dominated the course. Since 2006, the average winner of the Masters ranked 42nd on that year’s PGA Tour average-driving-distance list. Twice since 2006, the longest driver on Tour won: Bubba Watson in 2012 and 2014. But the winners also include Zach Johnson in 2007 (169th in driving distance), Patrick Reed in 2018 (T-83), Jordan Spieth in 2015 (T-78), and Trevor Immelman in 2008 (T-66).

The best example of distance versus finesse at Augusta National might have come during the fourth round in 2020. That’s when 63-year-old Bernhard Langer, averaging 260 yards for the week (but only 250 in the fourth round), outdueled his playing partner, 27-year-old DeChambeau, by a score of 71 to 73, and by one shot for the week, despite being outdriven an average of 65 yards per hole.

At Augusta National, position is everything, especially on the approach shots, where the combination of dramatic contours, steep outslopes, and firm, fast greenside conditions places a premium on accurate iron shots. Of course, distance is always an advantage; it’s much easier to parachute in accurately with an 8-iron than to try to stop a 5-iron.

The folks who run Augusta National pay a lot of attention to ground conditions, from constantly improving fairway drainage to making sure greens and surrounds run as firm, fast, and dry as the weather will allow. Their continually expanding use of Sub-Air drainage to vent and dry greens and surrounds is part of that effort. So, too, their block pattern of fairway mowing, consistent with agronomic studies that show that overseeded perennial rye of the sort used at Augusta National can create about two yards of drag that brakes the ball when the turfgrass is mown from green to tee.

It helps that the club maintains a comprehensive database of every club hit, every yardage played, every hole location, and every scoring sequence going back a decade or two. They also do an impressive job monitoring the course and tweaking it year to year to enable the ground-game features to interact more dynamically with players. This offsets considerably the distance advantage that elite golfers now enjoy.

One thing we might see—as soon as this year’s Masters—is for the club to make a decision with its first cut; either mow it down completely or grow it up. Taking it down to fairway height would dramatically expand the full width of the playing corridors and allow slightly offline shots to run into more pronounced angles of recovery or simply into the woods. Alternatively, they could grow the first-cut up to more than 1.25 inches deep, enough to allow the blades of grass to cover the equator of the golf ball, which would take the spin off approach shots and lead to a marginal loss of control. Either step would work to offset the distance advantage and affirm the importance of shotmaking.

Two things are for sure: 1) The folks at Augusta National have studied and considered all of this, and 2) they’re very good at keeping us guessing as to the next step in keeping their golf course relevant.