A relatively small, though certainly important, part of a golf course architect’s job is deciding on a hole’s cosmetics, or how it’s going to look. A more important layer for most is its strategy, or how it’s going to play. By far the most crucial consideration, however, as it pertains to the functional, operational, and financial success of a new course, is deciding where the holes will go in the first place.

Why the architect chose to arrange and position the holes as he did is something few golfers think about, but is absolutely the first building block in creating a new course. Tom Doak spells out how critical a course’s routing is at the start of his “Routing Primer” in Getting to 18—the mammoth book published through his own Renaissance Golf Publishing company which details how his first 18 layouts arrived at their final configuration.

“What golf course architects call routing—choosing the positions of tees and greens for every hole on the course—is the essence of golf course design,” says Doak.

Throughout the book, the reader learns that a good routing will visit the property’s most interesting parts, traversing or running alongside its most stimulating landforms and taking the golfer on an adventure that sustains his interest for the entire round. It will do its best to avoid parallel holes and playing into the setting sun. It will allow for holes of varied lengths and test players with winds from all directions. Above all, it will do everything possible to avoid monotony.

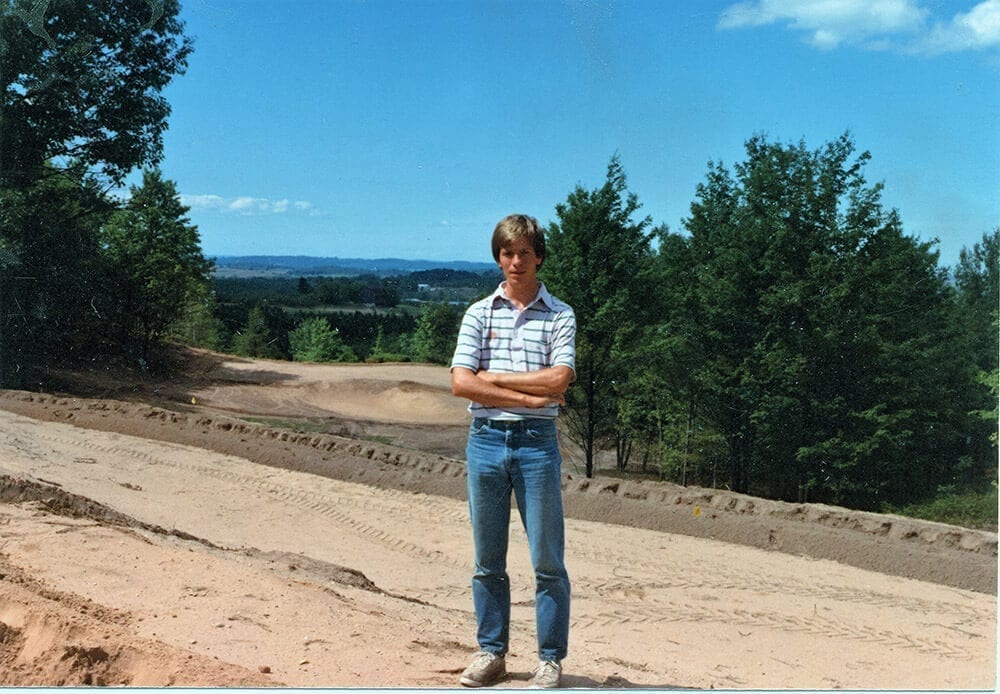

Despite the routing’s profound importance, Doak says he received no more than an hour’s formal training on the subject—a lesson that happened in 1981 on the site of Long Cove Club in Hilton Head Island, S.C., where, after three years of writing letters to the active designer he most admired, Doak at last got his opportunity to work on Pete Dye’s construction crew. Over sandwiches in the dirt, Dye told his young apprentice of his plans for the Honors Course in Chattanooga, Tenn.—lessons Doak says he has never forgotten.

His education advanced significantly a couple of years later when he was able to make copies of topographical maps from a selection of America’s most famous courses—Merion, Oakmont, Oakland Hills, Augusta National, and Winged Foot. In analyzing the contours on these maps and walking the courses, he could see how the map and the reality fit together—a process he calls a “revelation.”

Though topographical maps and routing plans play a vital part in telling the story of each course in Getting to 18, it isn’t just for cartographers who devour intricate, often mystifying, diagrams. An important addition to the book is the heretofore untold anecdotes Doak tells of his discussions, disagreements, and frustrations with team members, owners, government officials, and land planners.

Among them is the story of why the 10th and 11th holes at Pacific Dunes ended up as back-to-back par threes. Doak’s first plan, drawn up before he had a chance to see the final site for the course, encroached on 70 acres that David McLay-Kidd had been given and used for the resort’s original course. Doak’s drawing had included the current sites for the 10th and 11th greens, but the 10th was a short par four whose tee was now in the middle of Bandon Dunes’s 7th fairway.

“I realized the only way I was going to be able to keep those green sites was to have back-to-back short holes,” says Doak. “I knew that would be a hard sell, and indeed, it took some time for Mike (Keiser) to be comfortable with the idea.”

Doak also tells how he identified four distinct types of terrain at Bandon—a gorse-covered plain at the north end, a big valley along the eastern edge, a sandy bowl in the center, and the cliffs.

“My hope for the routing was to wander in and out of these areas as much as possible, like at Cypress Point, instead of tackling them one at a time.”

This compelling insight is a constant theme throughout the 211 pages of a book which took Doak two and a half years to write. His former employee at Renaissance, Sara Mess, dug out the 144 photographs and 121 maps, masterplans, sketches, and letters from old company files that illustrate the progression and complexities of the work, and explain why the first 18 courses in Doak’s remarkable career—from High Pointe in Michigan to Barnbougle Dunes and St. Andrews Beach in Australia—turned out the way they did.

Before embarking on the sizeable task of producing the book, Doak says he thought a good deal about what was missing from the literature of golf course architecture. Something on how to route a course seemed to him the biggest gap. With Getting to 18, that gap has been painstakingly and magnificently filled.

The book retails for $350—to purchase your signed and numbered copy, visit https://www.doakgolf.com/