This sporting renaissance woman of the early 20th century was a golf champion both on and off the course

Most histories of women in golf jump from Mary, Queen of Scots (who famously teed it up days after her husband was murdered in 1567) to Babe Zaharias, who won the U.S. Women’s Open in 1948, ’50, and ’54. Among those overlooked are such early-20th-century stars as Joyce Wethered, Glenna Collett Vare, and the Curtis sisters.

And Marion Hollins, a considerable oversight as she was considered one of the finest athletes of her day in two sports, and was instrumental in the creation of three of the world’s top golf courses.

A child of the Gilded Age, Hollins was born in 1892 on a 600-acre estate on New York’s Long Island. Her father was a Wall Street broker, her mother a descendant of the Mayflower. Theirs was a world of wealth and privilege, for whom, one friend said, sports was “the purpose of life.”

As a horsewoman, she became expert both in the saddle and from the seat of a four-in-hand carriage. She also was the best female polo player in the country, the only one to carry a men’s handicap. Later in life, she trained horses for steeplechase, a sport it’s said she brought from the east coast to the west. There’s even evidence that she was the first woman to drive in an automobile race.

Marion’s golf career started at age six. Competitive opportunities for women were limited, but beginning in her teens, she won them all: the Women’s MGA Match Play championship three times, Long Island championship twice, and the Pebble Beach Women’s Championship—an event she founded—seven times. At the major of the day, the U.S. Women’s Amateur, she qualified 15 times between 1912 and 1940, finishing runner-up in 1913 and winning in 1921.

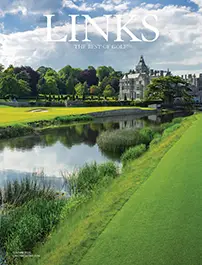

Shortly after that victory, Hollins headed west and went to work at Pebble Beach, selling real estate and bringing along her famous friends, from golfers to movie stars. To promote the Monterey Peninsula, she had the idea to create a private club, and so she developed Cypress Point.

Her original choice for architect was Seth Raynor, but when he unexpectedly died in 1926, she hired Alister MacKenzie, who unstintingly credited Hollins for one of golf’s most famous holes, Cypress’s magnificent par-three 16th. Both Raynor and MacKenzie envisioned a par four there, thinking the carry over the ocean was too long. Hollins disagreed and, wrote MacKenzie, “teed up a ball and drove to the middle of the site for the suggested green.”

Throughout the ’20s and ’30s, Hollins was bi-coastal, concurrently developing the Women’s National Golf & Tennis Club on Long Island. Designed by Devereux Emmet—with input from C.B. Macdonald and Raynor—it satisfied Hollins’s desire to build a course that suited women’s games. Despite early success, the club fell victim to the Great Depression.

On the west coast, Hollins invested in some oil wells, made a killing, and used the money to develop a golf community up the California coast in Santa Cruz. Again working with MacKenzie, they created Pasatiempo, which opened in 1929; now a world-class public course, it is one of the architect’s seminal designs.

Marion contributed to another notable course—Augusta National. In 1929, after her friend Bob Jones surprisingly lost in the first round of the U.S. Amateur at Pebble Beach, he hung around and played both Cypress Point and Pasatiempo, likely with Hollins. He also spent time with MacKenzie, leading to their collaboration in Augusta. And a few years later, when MacKenzie was unable to make an Augusta site visit, he sent Hollins as his “representative,” telling Clifford Roberts, “I do not know of any man who has sounder ideas.”

A car accident in 1937 began a long slide into depression and illness. Hollins died in 1944.