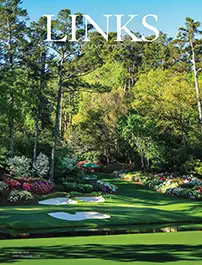

The characteristics of Augusta National’s greens—large, contoured, quick—create very different holes when the pin is moved.

The Masters distinguishes itself from other tournaments in so many ways, but one of the most fascinating is that competitors here aren’t playing the same 18 holes four times. Rather, they face 72 distinct challenges. There are obviously similarities between each of the holes from one day to the next, but at the Masters, Thursday’s 16th for example, is very different to Sunday’s.

“The course has changed a lot through the years, so the way players approach each hole—and the shots they hit—is very different now,” says Florida-based course architect Steve Smyers, who has been coming to the Masters for nearly 40 years. “Today you can hit the ball high and land it soft to much more of a degree than in the ’50s and ’60s, when the ball flew on a much lower trajectory and you really had to take the contours and angles into account. But Augusta still demands you decide your strategy for the hole as you stand on the tee (or before), more than anywhere else. It’s not just about hitting a well-executed shot here, it’s about hitting the right shot.”

Forrest Richardson, another course architect and devoted student of Augusta National, agrees saying the course’s greens are so large they give the course set-up committee so many options. “Augusta has greens within greens,” he says. “That’s a key concept with the greats of course architecture.”

Indeed, says Smyers, having a hole play so many different ways is a mark of greatness. “And having 18 of them makes the course truly special,” he adds.

Take the 3rd for example. This beguiling short par four can certainly be driven, but is often more sensibly played with a long iron and a wedge. Smyers remembers watching Tiger Woods approach the hole in various ways one year. “He hit the iron a couple of times, but I also remember him hitting a driver into the pine straw left of the green,” he says. “Everyone thought he had hit a big pull, but the pin was on the right, and it became clear he had purposefully gone left to leave himself an easy pitch across the green. He made a birdie.”

As pins move around, so each hole plays very differently. But which holes, besides the 3rd, require the most drastic change in approach when the hole is relocated?

“The green at the 2nd is so wide and so contoured, the shots it demands from one day to the next are obviously very different,” says Smyers. “When the pin is back left, players can hit a high approach that drops and stops near the pin. But when it’s right, they need to hit a lower shot that finds the slope and feeds down the hill to the hole.”

It’s much the same story at the par-three 16th, a hole that Robert Trent Jones defended with a large pond in 1948 (previously, a narrow creek had run diagonally in front of the green). “Many of the holes play very differently when the tee is moved too,” says Jones’s son Robert Trent Jones Jr. “The 4th is a great example, as is the 16th. On Thursday, the tee is up at 16, and the hole is usually cut short-right. It’s just a high wedge or 9-iron with some cut-spin to hold it on the slope. But on Sunday, when the pin is back left and the tee is all the way back, players typically hit a lower shot with a little draw that finds the back of the green and hopefully bends left before moving back down the hill toward the hole.”

The examples keep coming. The downhill par-three 6th is another hole where a front-left pin demands a totally different shot to a back-right pin. “If it’s on the shelf back right, you need to hit a high shot that stops quickly,” says Smyers. “If it’s front left though, you can hit it slightly lower and use the contours.”

Ironically, the most famous hole of all—Golden Bell, the utterly delightful but potentially very dangerous par-three 12th at the bottom of the property down by Rae’s Creek—might buck the trend slightly. “This is one hole where the same shot every day might actually be a sound approach,” says Smyers. “A stock short-iron to the middle of the green makes sense wherever the pin is. Differing winds and humidity might call for a slightly different shot each time, but the center of the green is always a good place to be. Of course, circumstances can change everything. If the player is feeling comfortable with his swing, and thinks he needs a birdie on Sunday, he’s probably going to chase that far-right pin.”

Changes in agronomy, equipment, and the athleticism of players have seen the demands Augusta National makes of Masters competitors evolve significantly through the years. The range of shots and angles Danny Willett used to win the green jacket in 2016 might not have been quite as wide as that of Henry Picard in 1938, for example, or Jack Burke Jr. in ’56, or Jack Nicklaus in ’75, or even ’86. But good strategy, imagination, and a full repertoire of shots are still so important. “I like to say the PGA Tour has become like Four Seasons hotels,” says Jones Jr. “Each hotel is wonderful, and the setting might be fantastic, but you basically know exactly what you’re going to get each time you go—similar linens, service, furniture, etc. It’s not like that at Augusta National. There are still so many variables, interesting physical and mental challenges, and unpredictable moments.”

And that, surely, is a large part of what makes Augusta National and the Masters so great.

_______________

What are your favorite holes and memories from the tournament at Augusta National? Let us know in the comments below!

Number 15 is my favorite hole, I enjoy how players decide to play it. Some players are willing to take the risk of going for the green in two while others lay up and hit a short shot into the green, regardless of how they play it they are attempting to play it under par.

Watching the MASTERS is the highlight of my television entertainment for

the year. No staff or collection of Hollywood writers could write a script to

match what we see every year on the final nine holes. Our Open, the Players,

the British Open, the PGA and the Ryder Cup all bring fun and excitement,

but not like the Masters.