For the vast majority of us, the Masters has been a very special and ever-present part of our lives, filling us with anticipation at the start of every April and giving us thrills and excitement few other forms of entertainment could ever hope to provide. And though it’s the youngest of the four majors, as far as most of us are concerned it’s been here forever and is the grandest show in golf, played at a celestial place somewhere in the universe (but clearly not this planet).

Depending on how old you are, however, and how easily you can appreciate that, in the grand scheme of things, 94 years is just the proverbial drop in the ocean, it really wasn’t all that long ago that things looked very different at Augusta National Golf Club. Yes, it’s always been a club for extremely wealthy individuals, but you only have to google “animals grazing on the grounds at Augusta National”; “lengths the club went to in order to attract players and spectators to the Augusta National Invitational”; “Fruitland Corporation defaults on loan”; “Augusta National Invitational in the red”; or “players who earned prize money at the first tournament and where the money came from” to know the immaculately presented, globally popular, mega-revenue-generating spectacle we now enjoy endured some lean times during the Great Depression in the early-mid 1930s.

And though we’ll always picture Bobby Jones first when thoughts turn towards Augusta National and the Masters, there are several people who played a significant part in their creation but who would be largely unknown were it not for Curt Sampson, David Owen, and Charles Price’s brilliant histories of the club and tournament.

You probably know about Clifford Roberts, the New York investment banker and friend of Jones who did so much to establish the club and promote the tournament while managing to develop a reputation for being a hard-nosed authoritarian for whom there was only one way to get things done—his. But here are some unsung heroes of Augusta National and the Masters to whom we should probably offer a silent “thank you.”

Thomas Barrett Jr.

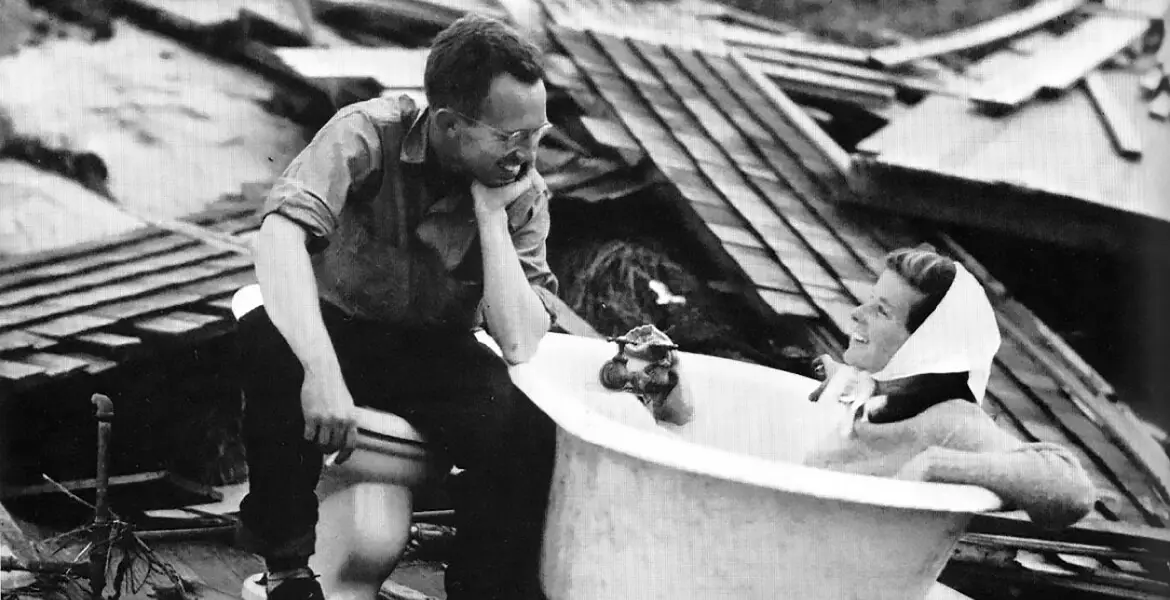

A prominent Augusta businessman, vice president of the Bon-Air-Vanderbilt Hotel, a war hero, and a very active member of the Augusta Chamber of Commerce, Barrett was the man who suggested the old Berckmans nursery to Roberts as a potential site for his and Jones’s golf club. The property had been owned by the Washington Heights Development Company and earmarked for a hotel to be developed by Commodore J. Perry Stoltz. In September 1926, however, a terrible hurricane hit southern Florida, destroying Stoltz’s Miami hotel and forcing him into bankruptcy. Five years later, on June 30th, 1931, the Augusta Chronicle announced the 365-acre property had been purchased by a group called the Fruitland Corporation (for $15,000 and by taking on the previous owners $60,000 debt) of which Barrett was President. Barrett wasn’t a golfer but had a great respect for Bobby Jones and was confident a Jones-owned/designed course in his home city would prove extremely beneficial.

One of the club’s earliest members, Barrett would become Augusta’s mayor in 1933 and help the club stage its first tournament by funneling $10,000 from the city to subsidize expenses. Barrett died shortly after the inaugural event, after suffering unexpected complications of 15-year-old war wounds. He was just 40.

Alfred Severin Bourne

Whichever book, document, or article you read about Augusta National’s formative years, you’ll see many refences to several deep-pocketed men whose funds saw the club and course get built in the first place and whose generosity ensured their survival during the tough years thereafter. It seems, however, the man who reached into his pockets the deepest was Alfred Severin Bourne, whose father had built the enormously successful Singer Sewing Machine Company and left his son $25 million in his will. Before Augusta National was built, Bourne played at Augusta Country Club to which he also donated money from time to time in return for his own locker room. He played regularly with Roberts who would later call on Bourne repeatedly to finance Augusta National’s progress.

Bourne’s initial gift to the new club/course was $25,000—a huge amount at the time but not nearly as much as he would like to have given. Had the Depression not wiped $10 million from his assets, Bourne said he would quite happily have paid for the entire project himself. He served the club as a vice president and as one of three members of its Beautification Committee which came up with the suggestion of planting certain trees/bushes/shrubs/flowers at each of the 18 holes.

John Derr

By all accounts—well Curt Sampson’s at least in his book The Masters—Golf, Money, and Power in Augusta Georgia—Columbia Broadcasting System (CBS) was fortunate to land the rights to televise the Masters, beginning in 1956. Cliff Roberts was initially courted by NBC and gave the company 60 days to agree to a deal. His letter, however, was sent by mistake to John Derr, a newspaper man from North Carolina who worked at Augusta National for the first time in 1935 and, 10 years later, began broadcasting for CBS Radio. Derr, who would go on to become head of CBS’s sports division, had become friends with both Roberts and Jones to whom he had been introduced by O.B. Keeler. After meeting with Roberts in New York to agree to terms (Roberts’s mostly), CBS got the TV deal, and Derr called the tournament for 41 years, meaning 62 Masters in all as a reporter, broadcaster, and announcer.

Derr might be the most unsung of them all, but he wasn’t the only CBS man to become a Masters legend, of course. Frank Chirkinian became golf’s most famous director/producer working 38 editions, while commentators Pat Summerall, Ken Venturi, Dick Enberg, Henry Longhurst, Ben Wright, Brent Musburger, Jack Whitaker, Vin Scully, Nick Faldo, David Feherty, Verne Lundquist, Jim Nantz, and a handful of others have described the action and the moments.

Ike and The Gang

Dwight Eisenhower first visited Augusta National on April 13th, 1948—a couple of days after Claude Harmon had won the Masters by five shots. He had been invited to the club by a member named William Robinson who had met Eisenhower during World War II and who was now general manager of the New York Herald Tribune. Even though the war had been over for three years, General Eisenhower—the Supreme Commander of the Allied Forces in Europe—was still a hugely popular figure wherever he went (well, maybe not Germany) and no doubt relished the prospect of the peace and quiet a club like Augusta National could provide.

Members welcomed the association between the General and their club. Friendships formed quickly, the Eisenhowers (Dwight and Mamie) soon felt comfortable, and the General was quickly made a member. Roberts soon became Eisenhower’s financial advisor and the club’s wealthy members/donors were instrumental in getting him elected President of the United States in 1953.

Ike (Dwight and his six brothers were all nicknamed “Ike” which apparently came from the sound of the family’s last name) visited the club 45 times over the years becoming especially close with a group of golfers, Bridge players, and hugely influential businessmen that he referred to as “The Gang.” Members of this ultra-exclusive clique, within an already very private golf club, included Bobby Jones and Clifford Roberts, Peter Jones (head of Cities Service—the forerunner to Citgo, and another candidate for the club’s and Eisenhower’s Presidential campaign’s most generous benefactor); E.D. Slater (whiskey); Bud Maytag (washing machines); Albert Bradley (General Motors); Robert Woodruff (Coca-Cola); George Humphrey (Secretary of the Treasury); William Robinson; and Alfred Bourne.

The club and Masters were pretty well established by the time Eisenhower arrived—who is, admittedly, far from unsung—and it’s debatable whether you could describe a circle of Bridge-playing, multimillionaire golfers as “unsung heroes.” But Eisenhower is an important part of the Augusta National story, and the image of a few mega-rich Augusta National members playing golf and hanging with a President who calls you part of his gang is so ludicrously fantastical it just adds to the lore of the place. And we love it. So, they’re staying.

Johnny Goodman

The link between Goodman and Augusta National is a little tenuous, perhaps. The club would have been founded regardless of the Nebraska native’s play at the 1929 U.S. Amateur Championship, and he, therefore, played no part in the conception, instigation, or evolution of the Masters Tournament. Were it not for him, though, it’s likely Bobby Jones wouldn’t have become quite so familiar with Dr. Alister MacKenzie’s talent—at least, not when he did—and might have chosen another architect, possibly Donald Ross (who had already worked in Augusta at Augusta Country Club and Forest Hills) to design his Georgia course.

Jones met MacKenzie at the 1924 British Amateur Championship in St. Andrews where they would have had the opportunity to discuss their mutual admiration for the Old Course. MacKenzie would also give Jones a copy of his book Golf Architecture that had been published in 1920. But Jones didn’t see MacKenzie’s work first hand until 1929, ‘thanks’ to Johnny Goodman.

Goodman became an orphan in his early teens after his father abandoned the family and mother died in childbirth. He got a job caddying at the Field Club of Omaha and won the city championship while in high school. In 1927, aged 17, he won the prestigious Trans-Mississippi Amateur, and, in 1929, qualified for the ’29 U.S. Amateur at Pebble Beach where he was drawn to play Bobby Jones in the first round.

Against the best player in the world who had beaten him by 12 strokes over 36 holes of stroke play (145–157) in progressing to match play, Goodman was given no chance of winning but somehow managed to take the match 1 UP (he would eventually go out in the round of 16).

Having been knocked out so unexpectedly, Jones was at a bit of a loose end the following day, so he arranged a game at a recently opened course a couple of miles away called Cypress Point. The following day, he accepted an invitation from Marion Hollins to play in the opening exhibition match at a brand new course, Pasatiempo, 50 miles to the north, getting his second dose of MacKenzie magic. Having played the two courses in quick succession, it’s not difficult to see why Jones would select the English physician for the job.

Goodman would play in the Masters only once—finishing 43rd in 1936. Three years earlier he had won the U.S. Open (the last Amateur to do so) at North Shore Country Club in Illinois, and he won the U.S. Amateur in 1937.